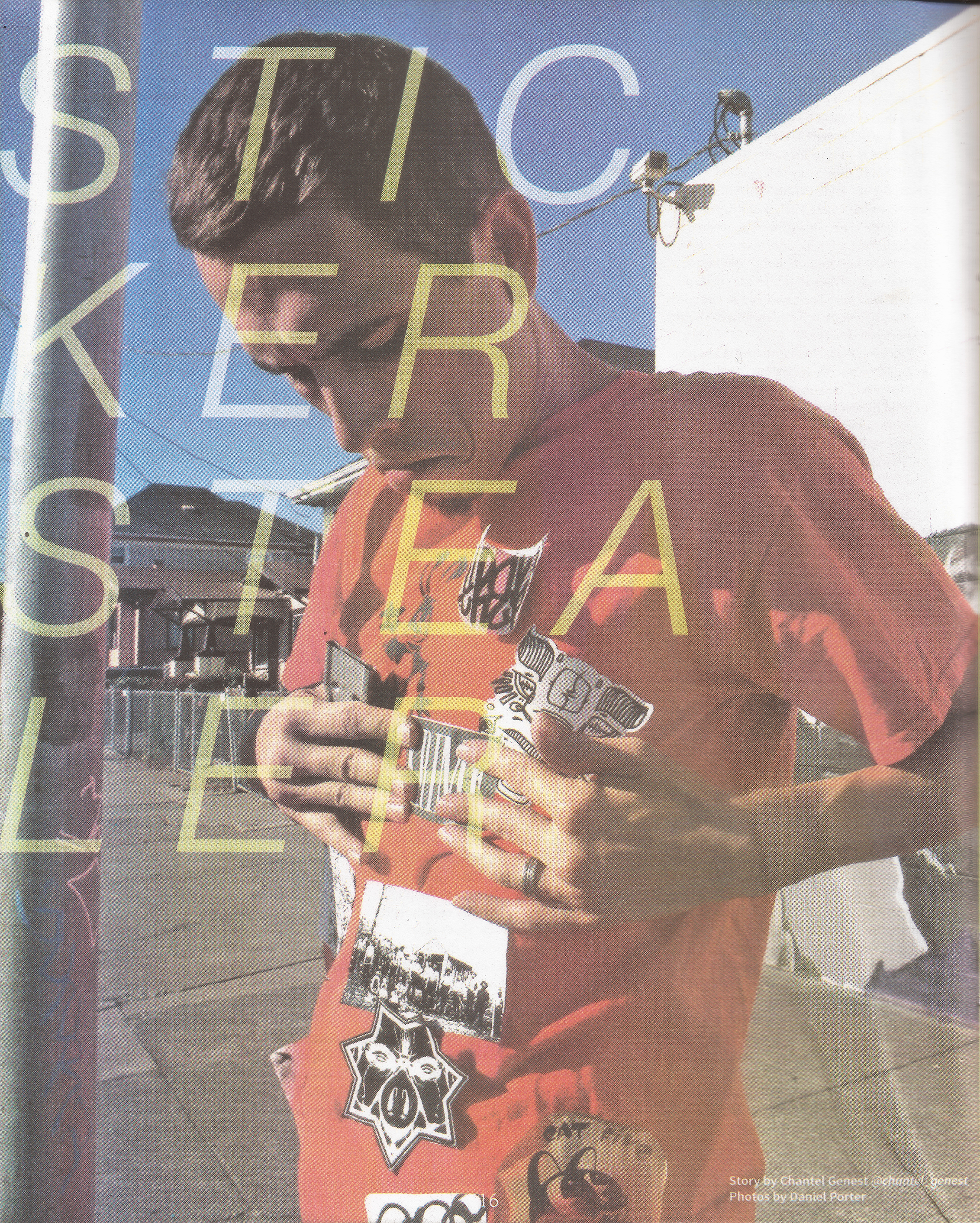

John R. Henifin places new stickers on his shirt from local graffiti artist he admires. (Photo Curtesy: Daniel Porter/Xpress Magazine)

Passersby walk their dogs and examine their phones as the wind blows, paying no mind to the man climbing up a streetlight in the middle of a busy sidewalk. One leg supported by the base, one arm hugging around the length of the pole, the Oakland resident scrapes and peels off a compilation of sticker art, previously placed on the metal signs directing pedestrians to public transportation near the intersection of Telegraph Avenue and 40th Street.

It is ten o’clock on Saturday morning and John R. Henifin sits at the MacArthur BART Station in Oakland, sipping a cup of coffee, earbuds blasting the Pixies, getting hyped for an afternoon of scavenging. The weather is warmer than usual and John takes off his brown Abercrombie fleece and heads out from the station. Within ten feet, he hands me his jacket; he has found his first canvas to empty.

The tall, green streetlight, filled from top to bottom with stickers of various sizes, is a storyboard of Bay Area art; a collection of political statements, advertisements, and personal messages. By the time we turn the corner, Henifin’s small blue v-neck is covered from front to back in the neighborhood taggers’ work.

“If someone likes my sticker enough to want to have it for their own collection, I think that is great,” says Danville sticker artist Mar Preclaro, twenty-three, who began putting up her stickers four years ago. “I liken street art to sand painting—both are beautiful and impermanent. For every piece that is scrubbed off or painted over, more appear to replace it. It reminds me that nothing in life is set in stone and if you want to leave a mark on the world, so to speak, you have to put in effort and be persistent.”

As we cross the street, the wind blows one of the stickers off Henifin’s shirt; it flies away and he dashes to catch up to it in the middle of the busy road, as the flashing red hand counts down the seconds. Able to grab the tag, he looks up and runs to the sidewalk, barely escaping the line of honking horns from disgruntled drivers.

This is just another day of collecting stickers for the twenty-seven-year-old. He carries his small, black satchel filled with razor blades, a multi-colored striped scarf, and a stack of four-by-six-inch hard fliers that he has collected from local coffee shops. His nails un-groomed, each one long enough to slide under the thin material he encounters, and already filled with dirt from collecting on his way to our meeting spot.

When there is no more space to fill on his upper body, he stops and puts all that he has gathered so far onto the back and fronts of the thick, glossy fliers. He does this to initially keep each piece in place without ruining them. The gloss takes the adhesiveness off the stickers and allows for an easier process when later placing them into the newest pages of his neatly organized binder collection, in which he will stack next to the excess of other binders on his floor-to-ceiling bookshelf at home.

“I often spend more time putting the stickers carefully into binders than I do removing them,” says Henifin. “On average, [I spend] twenty hours a week collecting and thirty hours a week sorting. Some days I will just grab a dozen or so on my way somewhere while other days I go out with a purpose and collect dozens.”

Since starting in 2009, Henifin has gotten the act of peeling and scraping stickers down to a science. He can tell how long a sticker has been posted there, what material it is made of, and whether or not he can get it off without it falling apart. His experience has given him the unique skill of knowing exactly when and where to look for stickers; finding them behind masses of plants, inside United States postal drop-off mailboxes, and one of his favorites – the large garbage can beneath the stairs at the MacArthur BART Station.

He calls himself the “Sticker Stealer,” a perfect illustration of what he has become, accumulating tens of thousands of stickers, creating his own archive of street art in the confines of his small apartment in Lake Merritt. His years of efforts are organized in binders by each month, a timeline of both consistency and change of artists who spend their days producing and printing masses of stickers to put on view. Henifin collects in Oakland, San Francisco, and anywhere he finds himself where stickers catch his eye.

“When I feel like I am ready and have enough, I will put it on display somewhere other than just online, hopefully touring it to different cities where people do not usually get to see Bay Area art,” says Henifin. “People often only think about what is in the here and now, but I am thinking this collection will be a lot more interesting in thirty plus years.”

Although Henifin enjoys collecting and saving stickers, his hobby stems from a sense of duty to himself and his community. He used to walk the same path to college every day and became annoyed by all of the pointless graffiti he would see and took it upon himself to clean it up. He also does other neighborhood cleanup like gardening, picking up garbage, and clearing water drains so that rain does not flood the streets. He has cleaned up abandoned properties and has gotten other neighbors to help with the gardening process too.

“I clean up the neighborhoods because of the positive response from the people that live in those neighborhoods, especially the business owners,” says Henifin. “I also like going to areas that I know will get tagged again because I feel it gives room for new blood and otherwise I watch it get layered, weathered, or discarded completely. With this, I get to help out my city and myself.”

Henifin keeps a razor blade on hand at all times and is always on the lookout for new sticker art pieces. A lot of the stickers are quite easy to get off of typical places that people post them: city street lights, stop signs, parking meters, and mailboxes. He gets the easy ones off first and then moves on to the harder-to-get pieces, trying never to spend more than a few seconds on each one, unless it is one he really wants.

As I ponder the reasons why anyone would waste their time collecting some of the less impressive pieces of work, Henifin explains the importance of getting a little bit of everything to show an honest reflection of all that is being put up in the neighborhood. Even the one-by-two-inch tags that give the impression of an elementary school kid attempting to graffiti his own name are found in this collection.

“I think people that put up stickers know that their art will not be there forever,” says Richmond sticker artist Andrew Snook. “By John collecting stickers, they have a chance of being preserved for a long time.”

We stop at a community mailbox outside of an apartment complex in West Oakland, a newly covered spot that Henifin had just recently cleared off himself. As he examines and peels, he offers stories of his encounters with the cops while out lifting stickers. Yet to be arrested, he has been followed and accused of placing bombs, defacing public property, and getting high, none of which held any evidence of truth. He has been physically thrown to the ground, had his property taken and broken, and been accused of lying on more than one occasion. After all this, he still continues with more passion and motivation than he ever thought he could have for such a trivial thing.

“I do not want artists to get discouraged just because there is someone like me out there who wants to share it with other cities, cultures, and decades too,” says Henifin. “Keep in mind that one person can easily put up more stickers in a day than I could take down, and I cannot go out every day.”

A native of Washington, Henifin came to the Bay Area in 2009. He has experienced months of homelessness, couch crashing, and has battled with fibromyalgia, a chronic musculoskeletal condition that causes pain and fatigue among other crippling symptoms, since 2003. As he climbs fences and paces down the busy streets, you would never guess he spent many years walking with a cane or that he was experiencing pain every minute of the day. He credits physical therapy, chiropractic care, and his loving dog, who literally stumbled into his lap one day out in the city, for his ability to walk without assistance now. He and his husband, a manager at a local 7-Eleven, have created a comfortable life in the Bay together. Although his partner does not approve of trekking through spider webs and grimy alleyways just to get a sticker, he has grown accustomed to Henifin frequently having to catch up while the two are out and about.

“I have always had collections, but this is the only one I have ever had that was really unique and not driven by money completely,” says Henifin. “I grew up collecting postage stamps, and then graduated to figurines and coins, but those all got expensive fast. Stickers has been the only hobby that I can do continuously without spending all of my cash.”

John R. Henifin organizes the stickers, he has collected, in the appropriate binder from local graffiti artist he admires. (Photo Curtesy: Daniel Porter/Xpress Magazine)

John R. Henifin organizes the stickers, he has collected, in the appropriate binder from local graffiti artist he admires. (Daniel Porter/ Xpress Magazine)

Henifin’s pursuits have led him to meet local artists and recognize those visiting the area, including one who approached him on BART: “This guy [sticker artist] saw me drawing on stickers and told me to look him up on Tumblr, now I cannot go anywhere in Oakland or San Francisco without seeing WasteFace [art pieces],” says Henifin. “Every sticker is really a gateway to a million more.”

As we pass a row of parking meters, a prime location for stickers, Henifin notices a tag of a small raccoon character. He identifies that the artist is from Seattle, whose work he has seen during visits to Washington. Being able to point out and tell me all about a sticker and the person who created it is an ongoing theme of the day.

His stories are endless, and his knowledge about sticker art and ability to identify almost every sticker that he sees is quite remarkable to watch. In a few hours, I become part of a culture, a world outside of my own, dedicated to a respect and understanding of this type of art’s purpose. We spend five hours on one ten-block radius alone without a dull moment or lack of art to hoard.

“Collections like John’s are good because people often walk past graffiti and think that it is a lower form of art or that it is not real art because it is not in a museum or because they think it makes the town look dirty,” says Preclaro. “But when they see them laid out neatly in front of them they start to notice details and look at it in a new light.”

As we near the end of our trail, a man sitting in his car starts to yell out at Henifin. He asks, judgmentally, what he is doing and why is doing it. Henifin explains his hobby kindly to the man and hands him one of his cards with his information and website on it. Henifin wishes the man a good day, despite his obnoxious laughing as we head toward the 19th Street Station. We wait for the train to take us back to where we started, and Henifin is still on the look out for more stickers, grabbing close to twenty more by the time the train arrives.

Along with collecting the stickers, Henifin makes and puts up his own stickers and has done dozens of collaborations, which he gives away to friends and strangers. He also trades and accepts “donations” in the form of stickers. There is no special underlying meaning in what he does and holds no greater reason for doing it other than for the sake of representing and saving art. Every day, artists spend their time producing art for no profit, for no gain, but solely to create. Instead of being criticized or seen as offensive, Henifin just wants it to be appreciated and remembered.

“Once it is presented in a different way, as art versus noise all over the street, people see it in a positive light and it changes the art completely,” says Henifin.

Scans Of Printed Article: